By Ginny Raue

WEST MILFORD — It’s said that knowledge and understanding can come from walking in someone else’s shoes. So slip on a pair of imaginary moccasins and walk back into West Milford’s history.

In the beginning

Massive boulders, deposited by a series of glaciers in the past million years, gave rise to rock shelters that were to become home to bands of Indians. The glaciers also formed rolling hills, terraces and lake bottoms that later enabled hunting, fishing and agriculture and an ideal place for the Lenni-Lenape Native Americans to call home. Or to be more precise, their seasonal home.

Archeological finds point to the supposition that Paleo-Indians hunted the wooly mammoth and mastodon in this area sometime between 12,000-8,000 B.C. Relics of a much more recent vintage indicate the presence of the Lenni-Lenape, meaning the “real people” or the “original people” in West Milford and surrounding areas centuries ago.

The Lenni-Lenape had migrated from the west to Mississippi and to the Ohio Valley. A great number of the Lenni-Lenape eventually settled along the Delaware and in present-day New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Who were the Lenni-Lenapes?

The Lenni-Lenape, later called Delaware Indians by English settlers, spoke in the Munsee dialect and were part of the Algonquin nation. They were a peaceful tribe, often serving as intermediaries within their nation. The Iroquois ridiculed them for their non-violent ways, disparagingly calling them “The Old Women.”

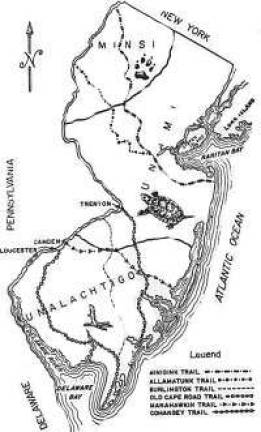

The Lenni-Lenapes of New Jersey were divided into three sub-tribes. The Minsi, or Munsee, meaning “the people of the stony country” lived in the northern part of the state. Anyone who’s put a shovel into the soil in West Milford would understand that. The Unami, “the people down the river” were in the central area and the Unilachtigo, “the people who lived near the ocean” were in the south.

Home sweet home

In the 17th century it appears that permanent villages were constructed along waterways, some as far north as the Great Falls in Paterson. The Lenape-built “long houses” were bark and grass covered domed buildings, some measuring 60 feet long. It is believed they were multi-family dwellings where the inhabitants lived and stored their food supplies.

In West Milford, the Lenape lived in rock shelters or in “wikki-ups,” temporary shelters of bark covered saplings. Three such camp sites have been located in the town, not far off Macopin (“place where wild potatoes grow”) Road. Favored camp sites were around Echo Lake, Greenwood Lake and the Pequannock River.

The rock shelters that have been discovered in West Milford were fortunate configurations of rock left behind a departing glacier. Soot from long-extinguished camp fires is still visible and in and around the town relics have been unearthed. The drought that plagued the area in 1963 proved a boon for those seeking Indian artifacts when thousands of objects were found under the Canistear Reservoir bed.

In the summer, like so many of today’s West Milford residents, the Lenapes headed for the shore. Not in search of a good tan, they went for the seafood. They harvested oysters and clams and enjoyed the cooler temperatures brought in on ocean breezes. As summer wound down they headed back to their camp sites up north, ready to harvest their summer crops of corn, beans, squash, blueberries, pumpkins, peppers and tomatoes and to prepare for the hunting season.

Daily life

Like most Native American Indians, the Lenape men dressed in breechcloths – a long piece of deer skin, fur or cloth worn between the legs, looped front and back over a belt and sometimes covered by an apron. They wore leggings, two separate, footless pant legs made of soft leather tied to the breechcloth belt and sometimes painted or adorned with fringe or beads. Women and teenage girls wore deer hide shirts and skirts. Infants wore diapers made of cattail fluff. Winter wear was often made of deer, bear and beaver skins and warm cloaks were fashioned of turkey feathers. While the Lenape often went barefoot, they wore buckskin moccasins in winter. Dyed deer hair was used for headdresses.

Making the best use of the readily available deer, the hunters sometimes camouflaged themselves in deer hide and made jewelry and hoes from the antlers. Sewing thread was made from sinew and needles from bone splinters. Tools were made of shell, bone, stone and wood.

Physical strength was an admirable quality and contests, such as tossing a pole through a rolling hoop, running and honing bow and arrow skills were part of their recreation.

Soups on

Corn was an important staple in the Lenape diet. It was served boiled, baked or fried in bear grease and was also used to make bread, soup and puddings. Boiled, baked and fried beans and squash were on the menu and herbs and greens spiced up meat entrees and soups. Food was cooked over a fire in clay pots or wrapped in leaf packets and set in hot ashes, then served in wooden bowls or on bark plates.

Get well soon

A Lenni-Lenape herbalist, it’s believed, had a good working knowledge of the healing properties of plants and knew what to do with them. The Lenape believed their creator had blessed the herbalist with the gift of healing. The herbalists learned their craft from the elders and thought themselves to be a conduit between the creator and their people. The healers prayed and held rituals before harvesting the healing plants.

Before the treatment started the herbalist would place the roots or leaves in running water. If they stayed afloat the patient would be healed. A sinking leaf or root, well, led to a sinking feeling that the patient was soon be headed to the happy hunting grounds.

Be sure to read part two next week: The Lenni-Lenape meet the settlers"

Sources: The Earth Shook and the Sky Was Red, Inas Otten and Eleanor Weskerna; http://Delaware.webs.com; http://fofweb.com; http://usgennet.org; http://en.wikipedia.org; http://native-languages.org