New book explains Kiryas Joel as product of Jewish history and American politics

UCLA Jewish history expert and USC law professor explore how Kiryas Joel came to be.

Since 2003, David Myers, an authority in Jewish history at UCLA, has visited the Hasidic village of Kiryas Joel dozens of times to discover what makes the insular community tick.

Meanwhile, his wife Nomi Stolzenberg, a professor of law at the University of Southern California who has written widely on law and religion, interviewed many lawyers who have either sued the village or represented it in the many lawsuits it has faced.

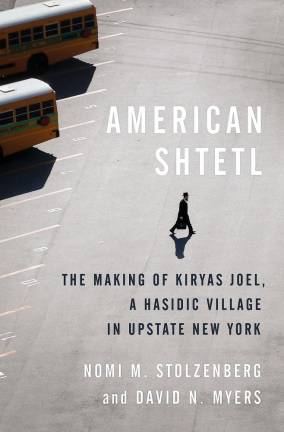

They have pooled their insights in “American Shtetl, The Making of Kiryas Joel, a Hasidic Village in Upstate New York,” just published by Princeton University Press (496 pages, $35).

The book is an evenhanded account of daily life in the village and of the conflicts spawned by its rapid growth. It will provide useful perspective for other Orange County residents, including those who scorn the village as a foreign growth in an apple-pie suburb.

“Our book is the first comprehensive account of the history of Kiryas Joel, extending back to the community’s origins in Hungary and continuing up to the present day,” Myers wrote in an email.

Myers said that he was fascinated by Kiryas Joel as “a case almost without parallel in modern Jewish history.” He found it “novel and fascinating” that it has been not merely a neighborhood or section of Monroe but a “legally recognized municipality” since 1977.

He said Kiryas Joel authorities welcomed his interest because “the community was interested in having someone hold up a mirror to it after more than a quarter century of existence.”

For her part, Stolzenberg emailed that she was intrigued by the battle over the creation of a public school district within Kiryas Joel, a years-long debate punctuated by a 1994 U.S. Supreme Court decision. She asked herself “how liberal rights could be used to empower a religious community that rejects modern liberal values.”

The 1994 case generated a flurry of interest in Kiryas Joel. How the Satmar leaders used their clout in Albany to win the school district was described in a 2016 book by Louis Grumet and John Caher: The Curious Case of Kiryas Joel: The Rise of a Village Theocracy and the Battle to Defend the Separation of Church and State,.

Stolzenberg emailed that none of reaction to the Supreme Court ruling “delved deeply into the history and inner workings of the community.” Myers added that he and his co-author spent a good deal of time unpacking the community’s many legal entanglements but aimed to situate them in a larger story about the Satmar and its “dual traditions of combativeness and accommodation.”

Is Kiryas Joel a theocracy, a town governed by what is inhabitants regard as the law of God? The authors have a measured answer to that question. Myers said the village, as opposed to the Satmars within it, is not governed by Jewish law. However, Stolzenberg said it could be argued that the distinction between public and private becomes fuzzy in practice with religious leaders controlling the selection of municipal officers.

Myers emailed that the Satmars have been “wildly successful in creating a full-service, Yiddish-speaking enclave that operates according to the community’s strict religious code and distinctive daily rhythm.” But the village’s need for land, sewage and water to serve its mushrooming population has introduced an “inescapable degree of tension,” with its neighbors, hampering harmonious relations.

When he came to America after World War II, Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, the charismatic founder of the Satmar Hasidic dynasty, sought to establish in Kiryas Joel (“Village of Joel”) a shtetl modeled after communities of European Jewry where his pious followers could be protected from spiritual pollution of the city

But the authors argue that Klryas Joel is, in many ways, a homegrown phenomenon. Myers emailed that it is far more homogenous, segregated and politically empowered than any Jewish community in the European shtetls of yore.”

The authors point out that that strong religious communities like the Puritans and the Mormons have always found a place in America and say Kiryas Joel is in that tradition. Moreover, the Satmars have learned the game of American interest group politics and “play it well.” They characterize as “unwitting assimilation” their use of American political and legal norms to achieve their goals.

If Kiryas Joel is a shtetl, “it is a decidedly American one,” the authors write in in their book, “rooted in the landscape of this country, inescapably subject to its social, economic and political currents, imprinted with traits that would have been unimaginable to the European shtetl and that clearly reflect is American provenance.”