Kratom revisited

UPDATE. A year ago, we published one family’s story of how their son died after using one of the unregulated supplements that the news media calls ‘gas station heroin.’ We return with an update about what RFK Jr. now calls ‘legal morphine.’

Nov. 2 will mark three years since my wife got a phone call telling us that our son, Brendan Mullally, was lying dead by the side of the road.

Brendan had suffered a seizure after taking kratom, a readily available plant-based substance sold for its properties to boost energy, ease anxiety or reduce pain.

It wasn’t the first time he had taken kratom. And it wasn’t the first time he had had a seizure after taking it.

Beth and I wrote about that day in an effort to bring attention to this drug we knew little about but whose effects will live with us until we die.

At that time, a handful of publications and media outlets had produced stories about kratom, typically because someone had been injured or died after using it. More times than not, though, most people had never heard of it.

Much has happened since then. Many states, including New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania, either have or are considering restricting the use of kratom or banning it altogether.

Kratom use also appears to be increasing. From Jan. 1 through July 31 of this year, poison centers across the nation have received 1,690 reports of exposure cases involving kratom. “This total has already passed the total from all of 2024,” said Shauna Devitt, the administrator at America’s Poison Centers (poisoncenters.org).

There also is a new urgency because of a powerful new derivative of kratom - 7-Hydroxymitragynine. 7-OH is a synthesized, concentrated byproduct of the kratom plant.

On July 29, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will take steps to restrict access to 7-OH products due to their strong opioid effects. These products would be regulated under the federal Controlled Substance Act. Such a move would make 7-OH products illegal like heroin, ecstasy and certain classes of fentanyl, among many others drugs.

At the press conference with RFK Jr. announcing the action, FDA Commissioner Dr. Marty Makary said there are many unknowns about kratom and 7-OH.

“7-OH is not just ‘like’ an opioid, it is an opioid” said Makary in a N.Y. Post story from the press conference in describing the compound as 13 more times more potent and morphine. “And yet it is sold in vape shops, in smoke shops, in convenience stores, in gas stations that are popping up around the United States. And no one knows what it is.”

What’s being done legislatively

Unless the federal government acts, any regulation will be left to the states:

N.Y. Gov. Kathy Hochul signed legislation in July 2025 regulating its sale in New York. This legislation prohibits the sale of kratom to individuals under the age of 21 and imposes civil penalties for violations. The bill also directs the State Department of Health to study the impacts and prevalence of kratom use in New York.

In Pennsylvania, Rep. Jim Prokopiak introduced legislation in September to regulate kratom by prohibiting the sale of the product to anyone under 21 years of age as well as require clear labeling regarding ingredients, usage and safety. It has not reached Gov. Josh Shapiro’s desk.

New Jersey legislators seem to be of two minds. “While some lawmakers see regulation as the best way to ensure safety, others believe both kratom and 7-OH should be pulled from the shelves altogether,” according an article by Jackie Roman in NJ.com.

Meanwhile, Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin have completely banned kratom. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia now have some form of kratom regulation, driven largely by concerns about product quality, age restrictions and public safety.

Brendan’s story

Although some progress has been made toward protecting people from Kratom, there is still much to be done. It is still up to us to protect those we love. For that reason, we are re-running the column from March 15, 2024 about Brendan Mullally’s death by kratom.

Headline:

When you get a phone call saying your son is lying dead on the side of the road

My wife’s cell phone rang shortly before noon on Nov. 2, 2022 – the Day of the Dead, according to my iPad calendar.

It was Emma Voegelin, a friend of Brendan’s. Beth’s son Brendan. My stepson.

The conversation was confusing. Emma said a friend of hers – someone we didn’t know – had seen Brendan lying on the side of a road. Emma didn’t know what road. Her friend was sobbing on the phone. “I tried CPR,” she told Emma. “But it didn’t work. It was too late.”

With this scant information, Beth and I got in the car and headed from our Goshen home to Brendan’s in New Paltz. We didn’t know where else to go. What road? Who gave him CPR? Had there been a car accident? We were both terrified and confused but we knew that, at the very least, we had to get Brendan’s dog Ozzie.

Lost in our own thoughts and fears, we barely spoke during the 40-minute drive. As we approached his road – his home was on the corner of Albany Post Road and a dirt road leading to a winery – we were shocked to see that his driveway was filled with cars. Cars with flashing lights. State police. An ambulance. The county medical examiner. Others.

And in the midst of the cops and EMTs, there was a white sheet spread out on the lawn. As soon as we saw that sheet, we knew. We knew that lying beneath it was the body of our son. Brendan. Brendan Mullally. Age 48.

He was, indeed, dead at the side of a road.

We would learn three weeks later, when the toxicology report was released, that it was kratom that had killed him.

‘Gas station heroin’

Kratom is used to alleviate depression, anxiety and pain. It is also described as a dietary supplement that may help those trying to withdraw from other drugs, such as fentanyl. It can prompt euphoria. And it can kill, primarily by causing severe seizures.

But the companies that market kratom take no responsibility for how it’s used and do not offer advice on dosage.

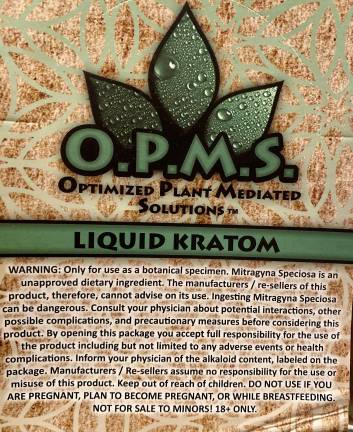

On an empty box that had contained liquid kratom found in Brendan’s house after his death, the following “advice” was printed:

“Only for use as a botanical specimen. (Kratom) is an unapproved dietary ingredient. The manufacturers/re-sellers of this product, therefore, cannot advise on its use .... By opening this package, you accept full responsibility for the use of the product including but not limited to any adverse events.”

In other words, if you die it’s your fault, not theirs.

Despite the danger, kratom is not regulated by the Federal Drug Administration unlike pharmaceuticals, cigarettes and alcohol. Instead, it is one of several over-the-counter so-called supplements sold at smoke shops, convenience stores and gas stations in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

Recent stories in the New York Times, the Washington Post and on the PBS News Hour describe kratom and similar products as “gas station heroin” because of its availability.

Brendan

Brendan was no stranger to drug and alcohol abuse. He struggled with addiction on and off throughout his teens and into adulthood, but his periodic falls off the wagon did not prevent him from success – both in business and personal relationships.

He graduated from college and, in his 30s, he created a successful moving company. BeeLine Moving and Hauling began with a small box truck and a used trailer. Working mostly in Orange and Ulster counties, he would come to donate unwanted furniture to Habitat for Humanity, one of his grandmother’s favorite causes. He also created a profit-sharing program for those who worked for him. By the time he died, the company was moving high-end furniture and antiques up and down the East Coast.

His greatest pride, though, was in his daughter Devon – a beautiful, smart, thoughtful young woman who was 15 years old when Brendan died. It was Devon who wrote her father’s obituary, which included this excerpt:

“Lately all of our best memories have been flooding my head. The nights we would sit out on the porch staring at the moon, waiting for rhymes to come to our minds so we could write them in my moon journal for school. You always had to force me to do it, and now I want to more than anything else. I miss walking in the woods with you. I miss sitting at the dinner table eating your world-famous chicken tenders with rice. I miss you. I love you. And I wish I had told you that more.”

‘Tell them Brendan’s story’

Ozzie lives with us now. He’s a little bit nuts – most Australian shepherds are – but he is an incredibly sweet, loving dog. Hugging Ozzie feels a bit like hugging Brendan.

Beth is still angry at Brendan for dying. She says she hopes there’s an afterlife so she can find him, yell at him, shake him, then give him an Ozzie hug and never let go.

As for me, my mind keeps wandering back to the little boy who graciously accepted me as his stepfather; who often sat on the couch between his mother and me wearing his little blue bathrobe and white tube socks; who raced through the house with me when we turned out the lights to have a rubber band battle.

We don’t know why Brendan was using kratom. To treat depression? Maybe. To treat the chronic pain in his shoulder that never healed well after surgery? Possibly. For the euphoria? Could be. To help him get off another addictive drug? Perhaps, but no other drug showed up in the toxicology report. Only kratom.

Brendan should have known how dangerous kratom is. He knew a great deal about drugs. But there are others – maybe those who are simply curious – who might be tempted to give it a try. Maybe even your own kids.

It’s just so easy. All they need to do is wander down to the nearest gas station or vape shop or convenience store. It’s sitting right there on the shelf.

If you have kids, or even older family members who are in the drug culture, talk to them. Tell them Brendan’s story. Talk so that you never get a phone call saying your son or daughter is lying dead on the side of the road.